The following piece was written in June, 2012 as part of my PGCHE studies with the Univeristy of Kent. The theme is Technology in the Academic Environment. The appendices mentioned throughout have been omitted in this version.

Improving screencasting processes: An Instructional Designer’s perspective.

by Tim Bones © 2012

The aim of the essay is to investigate the numerous instructional considerations required to produce screencasts for use in an exclusively online learning environment. As someone who has used various technologies to produce such learning materials, my aim is to use existing research, my own experience and student feedback to enable me to discover and utilise methods to make considered improvements to my own approach to planning and making screencasts.

What is screencasting?

John Udell along with Deeje Cooley and Joseph McDondald are credited with coining the term in 2004. Udell describes screencasting as,

“…a digital movie in which the setting is partly or wholly a computer screen, and in which audio narration describes the on-screen action. It’s not a new idea. The screencaster’s tools—for video capture, editing, and production of compressed files—have long been used to market software products, and to train people in the use of those products. …The medium, along with a new breed of lightweight software demonstrations, inspired the collaborative coining of a new term, screencast.”

Screencasting is also occasionally referred to as a ‘screen capture’ (JISC, 2010) & (Clarke, 2004). These terms are sometimes used interchangeably along with the term ‘webcasting’. However, (DiMaria-Ghalili, 2005), makes a further distinction between these, describing webcasting as an “instructional technology used to deliver audio and video presentations via the Internet, enabling learners to participate in a live class via a personal computer.” The live participation referred to also relates to webinars and online conferencing and are therefore distinctly different to screencasting.

For the purpose of this essay I am using the term screencast to describe the audiovisual recording of reusable screen-based software tutorials or demonstrations that are then placed into a Content Management System (CMS) for student access.

Context

Between October 2007 and September 2009 I began authoring and producing various visual and text-based instructional materials for an exclusively online learning environment, designed for undergraduate students of Graphic Design and Illustration. These instructional materials included screencasts. The company delivering these courses is the Interactive Design Institute (IDI). IDI’s courses are delivered globally via the content management system, Joomla. The University of Hertfordshire validates their courses.

In the summer of 2011 I resumed working for IDI and was once again requested to produce a large number of instructional materials, many of which took the form of screencasts. The current cohort totals 243 students across levels 4, 5 and 6.

Due to the frequent updates to design software such a Adobe’s Creative Suite—which is the design industry’s standard software—and in response to tutor and student needs made every semester via feedback sheets, these materials require regular revisions. As such, it is my intention to make the focus of this essay a means of identifying new, alternative and improved processes to the planning and production of screencasts and in turn improve my approaches to making screencasts.

The screencasts are designed primarily for the 150 Level 4 graphic design and illustration students for whom it is specifically expected that they will be able to “demonstrate a knowledge of the underlying concepts and principles associated with their area(s) of study”, and to develop a “sound knowledge of the basic concepts of a subject.” (QAA, 2008) As such, the instructional content of the screencasts is used to demonstrate design software techniques to the largely uninitiated student designer. These short demonstrations provide the requisite technical skills required to complete each practical element within a module and design brief, giving the student designer the foundational scaffold to progress throughout the given modules. The student is then able to watch these as many times as they need and these ‘movies’ can be paused at any point, thus giving the student ample time to watch and perform each step of the activity that is being demonstrated.

IDI’s online learning environment is essentially a lecture-less one. There are no formal lectures or face-to-face tutorials. Instead the students have access to a large body of structured instructional materials and a tutor (per module) who can be contacted online at any time.

Why use screencasts?

“The inclusion of video-based instruction in online environments, such as screencasting can have positive effects on student learning and can be pedagogically equivalent to their face to face instruction counterparts.” (Sugar et al, 2010) Sugar adds that “the combination of sound and images within a screencast enhances online learners’ experiences compared to the more traditional text format and can be a powerful method of communicating content in an online setting…[screencasting] should have a positive effect on learning because it provides multiple input channels by presenting an expert performing and describing a task.”

On assessing IDI’s instructional needs, it certainly appears that there is little in the way of effective alternatives to screencasts for teaching these essential skills to online design students. Apart from using text and image heavy documents, the screencast is arguably the most effective and succinct form of the demonstration that I could give that closely mimics what I do in face-to-face environment. For the practical activities required for graphic design, this appears to be the most logical, well received and most requested method of instruction for my online students. One alternative might be the webinar or online conference, but these could be problematic in terms of organizing both technically and in terms of getting tutors and globally spread students to come together at one convenient time. However, this activity could potentially be recorded and it too used as a screencast.

As well as arguably having to use them, many of my students respond positively to screencasts (see survey appendix A), this is largely because they are able to repeatedly replay the demonstration and pause it when needed. Also, one only has to scour sites such as Youtube or Vimeo to see the plethora of instructional casts that are growing exponentially, especially for creative software tuition, possibly indicating that screencasting is indeed a logical method of demonstration in the absence of face-to-face tutoring. (Luterbach et al, 2009) might support this notion, stating, “Because screencasting captures desktop activity along with audio commentary, it can be a particularly effective method of explaining computer-based procedures; this can be helpful for distance education situations where students may not have an opportunity to directly observe the instructor compete the task.” I should that I advocate students using opensource tuition to compliment the screencasts provided to further their skills.

Other advantages of screencasting materials might—withinan online context encourage, if not force independent activity. Anderson, 2008 states that “While screencasting provides a form of content and academic scaffolding, our concern is to ensure that students develop the skills to self-regulate their own performance and become aware of the gaps in their understanding of complex conceptual tasks. Effective learning is only guaranteed if learners are actively engaged in processing the learning resources.”

Millunchick et al (2010) encourage the making of screencasts to explain what he refers to as muddiest points, these are “supplemental screencasts that clarify topics that the students themselves are unclear.” He does this if more than 30% of his students request it. This brings to mind some of the comments raised in the survey (Appendix A) in which students suggested that non-technical screencasts would help support their understanding of some of the more abstract concepts associated with design such as visual semiotics.

Identifying, considering and utilizing effective approaches to screencasting

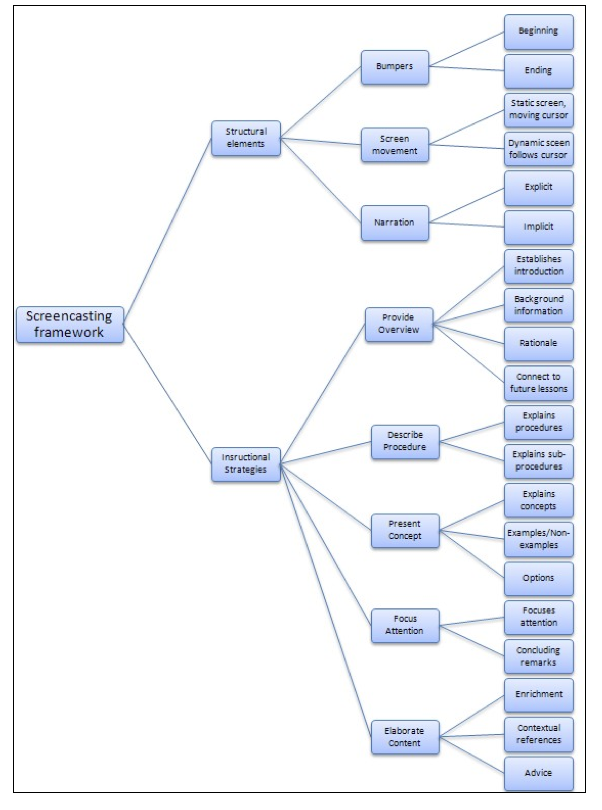

Sugar et al (2010) and Oud (2009) both identify points to consider for the building of screencasts. Of particular note were Sugar’s observations of the screencasts of his colleagues from various faculties within his university, where his research group identified a range of common structural elements present within each screencast observed. (Figure 1)

Within this structure Sugar identifies the following common elements of a screencast and divides these into two categories: structural elements and instructional strategies. The three common structural elements are “bumpers, screen and narration”. In short, ‘bumpers’ are the opening and closing comments within a cast; ‘Screen Movement’ this refers to the way in which the instructional designer leads the viewer’s eye around the screen, and finally ‘narration’.

In terms of identifying instructional strategies, Sugar identifies the following;

- Provide overview

This places the topic of the screencast into context - Describe procedure

Providing procedural knowledge - Present concept

Explanation of a specific concept - Focus attention

This can be said to be the drawing of the viewer’s attention to a specific part of the screen or software, such as in Figure 2 where in this screencast still for an Adobe InDesign tutorial I have used a device to not only magnify the part of the screen that I want to draw attention to, but this simultaneously darkens the parts of the screen not being discussed. - Elaborate content

This elaboration is where the instructor encourages learners to “consider other aspects of the process or concept associated with screencast’s subject matter.” An opportunity to make links to other learning and materials. This is something that I intend to develop within my own work.

Conclusions and Survey

The method that I have employed to make screencasts is based upon a system that I have been using since 2006 when I conducted a small-scale action research project. My original approach to designing learning materials, including screencasts was fairly straightforward and the outcome was as largely dictated by both financial and time constraints as much as by any instructional design (ID) model for online learning. The process used to design the materials was one of the many forms of the classic ADDIE model, refined by Dick & Dewey in 1978. The model identifies five phases for ID, these are:

- Analysis

- Design

- Development

- Implementation

- Evaluation

In the past I have perhaps planned, and, to a lesser degree, produced my screencasts in a somewhat implicit manner, using a relatively loosely mechanical ADDIE formula, much which works reasonably well, and indeed since researching this topic the student feedback has confirmed that much of what I do is good practice, but also that there is scope for widening my approach to the planning phase to successfully address any instructional needs in any future cycles of redevelopment of the screencasted materials that I produce. In the subsequent remaking of my current screencasts I have begun to consider Sugar’s instructional and structural points and I now consider most of these in a more conscious manner than I had previously. For example, I am now using a screencast planning checklist (Appendix B) largely based upon Sugar’s observation checklist structure (figure 1). As well as a widening my approach to screencasting, this investigation also suggests that I might expand upon the content of the screencasts too, and encompass more theoretical topics such as semiotics and approaches to essay writing, as these too have been suggested in the survey. (Appendix A)

I have always kept my screencasts short for both practical and psychological reasons. The practical being that large file sizes have, in the past, been difficult to produce and on occasion have proved difficult to stream, but also I have taken into consideration how much information a student can cope with in one session of online instruction. Oud, (2009) stresses the importance of considering cognitive load, and to be aware of the limitations of memory when creating multimedia-learning materials. Oud makes the assumption from one particular study that multimedia is more difficult for learners to process, as it places demands on our short term memory and suggests that multimedia is potentially useful in many situations, such as showing processes in action—which is precisely what my screencasts do. Oud suggests keeping the content of the screencast simple. I agree with this and I certainly never make long movies, instead I tend to break each topic down into small manageable stages for the student. For example, if teaching typography, I might look at letter spacing in one cast, line spacing in another, choosing typefaces in another, and so on. This is largely the approach I would take in a face-to-face session; tackling a large design problem by breaking it down into simplified stages and sections.

Small Scale Survey

I conducted a small scale, 10 question survey to elicit qualitative feedback (Appendix A) so that I might be able to ascertain how the students both perceive and use the screencasts, and in turn, help identify how I might make future improvements to any of my screencasts.

The key findings of this were as follows:

58% of students viewed all of the videos provided. When asked how they chose which videos to watch, a few of the comments suggested that some of the respondents possessed a prior knowledge of the software, and as such felt that they did not need to watch them. This may be because of prior work experience or because they could be a level 5 or 6 student and had covered most of the videos during level 4.

83% said they watched them more than once. One respondent explained that, “I use the training movies when I need them and when I don’t understand a part I watch again”, and another said that, “I use them if the video content is something new to me, or something that I do not know about. It is especially useful for students who have no prior knowledge of Adobe products.” This is good as this is largely the function of the movies; the student can watch them until they become proficient in a range of specific technical process.

Some of the comments—possibly from more experienced students—suggested that the screencasts were quite basic and as such I am now considering compiling a greater repository of screencasts with intermediate and advanced techniques to further challenge students.

Of their perceived usefulness, one student remarked that “The training movies are very useful as they are explained/shown step by step”, and “They help you to use the software and it’s easier to follow a movie rather than wade through lots of text.” Again, on the perceived benefits of not wading through texts, another said, “I love the IDI training movies, they present information across clearly. Personally I would rather listen to a training movie for 10 minutes than read over course materials as it is more engaging.” Students for whom English is a second language may find the illustrated nature of screencasts easier than written instruction too, as this student’s comment suggests, stating that “Sometimes [it] is difficult, especially when English is not your native language, to catch small details just based on naked text.”

75% of respondents also said that they would find non-practical or theory based subject matter conveyed via screencasts useful. The types of things that students suggested included “the working processes behind visual communication and theoretical based topics of study.” These included suggestions for essay writing and other contextually framed topics such as semiotics/communication theory. It could be that students simply wish to avoid reading texts, but again for the theoretical aspects of the course it was suggested that screencasts could have a role in mimicking face-to-face lectures as this respondent remarks, “There is a lot of reading already in that module CCS [Cultural & Critical Studies] it would be good to watch and listen as a different learning method (and more like a lecture).”

Similarly, another student requested “Anything that could be more like a lecture? I watched a number of lectures on line (from designers etc.) but might be good to have some from the tutors on the subject in general – maybe as an introduction/overview of the module.”

Students it seems are requesting traditional methods of teaching within the screencast. In light of the previous comments, I am keen to utilise the pooled knowledge of the 12 tutors to gain a greater breadth, scope and delivery of screencasted content.

Students made very specific additional software tutorial requests. Some of these could be considered for the repository mentioned earlier. One student suggested that they have access to a far fuller bank of screencasts similar to Lynda.com which is a software training & tutorial video library.

Other requests included:

- Extra effects in software [such as ] adjusting photos

- Design processes. E.g. Transferring sketch work to digital. Colouring sketch work in a digital environment. – Utilising digital media within mixed media experimentation.

- Other effects tutorials (e.g. How to develop a glass effect in PS, how to produce 3D text in AI etc.)

Other concluding thoughts

- Individual needs are not addressed throughout the technology and no quick scans or assessment methods are used by IDI that might inform the instructional design process.

- I perhaps should add that I have used screencasts as a resource for my face-to-face students and found that these are rarely used or accessed; the students instead preferring to wait until they could ask me for assistance directly.

- Something that the research does not investigate is accessibility; any screencasts that I put online at college would have to be submitted to the college’s deaf support unit six weeks in advance of it being used in order to provide a full transcript. I have broached this issue with IDI, and although they have no deaf students as yet, I feel that our provision should be ready to include such students. Some of the new screencasts that I have made have limited captions and some have been silent (some student expressed a dislike to the latter). I have made enquiries within the deaf community and have discussed the need for screencasted materials to be captioned, albeit in summarized form. This is something that I will suggest to IDI that we do to improve the accessibility of learning materials. I have begun to do this, as can be seen in the screen shot in figure 3.

In short, the research around the topic of screencasting I found to be largely as I expected. Most of the practices discussed were what I would deem common sense approaches to this type of instructional design. However, the structures and checklists for planning will be particularly useful to help ensure content is properly structured and documented. It was the students’ comments that I found to be most revealing and potentially useful, particularly those that leave me in little doubt that in the potential for using screencasts to deliver graphic design can go beyond just technical instruction and perhaps provide a more engaging and richer online learning experience.

References & Bibliography

Anderson, T (2008)

The Theory and Practice of Online Learning

Abathasca University Press

Brown, A., Luterbach, K. & Sugar, W. (2009).

The Current State of Screencast Technology and What is Known About its Instructional Effectiveness.

In I. Gibson et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2009 (pp. 1748-1753).

Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/30870.

Clarke, A, (2004) pp116

e-Learning Skills

Palgrave Macmillan

DiMaria-Ghalili R.A, Ostrow L, Rodney K.

Webcasting: a new instructional technology in distance graduate nursing education.

J Nurs Educ. 2005 Jan;44(1):11-8.

Jin, S & Boling, E, 2010

Instructional Designer’s Intentions and Learners’ Perceptions of the Instructional Functions of Visuals in an e-learning Context.

Journal of Visual Literacy, Volume 29, Number 2

JISC (May 2010)

Creating New Digital Media: Screencasting Workflow

Accessed November 2011?

Oud, J, (2009)

Guidelines for effective online instruction using multimedia screencasts Reference Services Review, Vol. 37 Iss: 2, pp.164 – 177

Accessed online 28/2/12

Oud, J, (2011)

Improving Screencasts Accessibilty for People with Disabilities: Guidelines and Techniques. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 16:3, 129-144

Kopel, M, (2010)

Ch. 28 The Paradigm of Screencasting in E-Learning

Advances in Multimedia and Network Information System Technologies

Nguyen et al (Eds)

Springer Berlin / Heidelberg

Loch, B & McLoughlin, C

An Instructional Design Model for Screencasting: Engaging Students in Self-Regualted Learning

Ascilite, 2011

Nguyen, F. & Colvin Clark, R. (2005)

Efficiency in e-Learning: Proven Instructional Methods for Faster, Better, Online Learning

The eLearning Guilds

Learning Solutions, November 2005

Pinder-Grover. T, Green. K, & Mirecki Millunchick, J. (2011)

The Efficacy of Screencasts to Address the Diverse Academic Needs of Students in a Large Lecture Course.

Advances in Engineering Education, Winter 2011

Parrish, P. (2009)

Aesthetic decisions of instructors and instructional designers

Accessed online

Peterson, E (2007)

Incorporating Screencasts In Online Teaching

The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning (IRRODL)

Vol 8, No. 3 (2007)

Accessed online 3/3/12

QAA, 2008

Framework for Higher Education Qualifications

Accessed online 12/12/11

Sugar. W, Brown. A, & Luterbach. K (2010)

Examining the Anatomy of a Screencast: Uncovering Common Elements and Instructional Strategies.

International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. Volume 11, Number 3.

Traphagan, T, Kucsera, J & Kyoko, K, 2009

Impact of Class Lecture Webcasting on Attendance and Learning

Education Tech Research Development 58: 19-37

Udell, J. (2005)

Screencasting’s one-year anniversary

Online Accessed 24/2/12

http://jonudell.net/udell/2005-11-18-screencastings-one-year-anniversary.html

Veldof, J

Creating the One-Shot Library Workshop: A Step-by-step Guide

ALA Editions, 2006

Zhu, E & Bergom, I, 2010

Lecture Capture: A Guide for Effective Use.

CRLT Occasional Papers, University of Michigan, No.27

Accessed online March 28, 2012

http://www.crlt.umich.edu/publinks/CRLT_no27.pdf