“Friday was St George’s Day. St George for England. I suppose the ‘England’ means something slightly different to each of us. You may, for example, think of the white cliffs of Dover, or you may think of a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe, or perhaps a game of cricket at Old Trafford or a game of rugger at Twickenham. But probably for most of us it brings a picture of a certain kind of countryside, the English countryside. If you spend much time at sea, that particular combination of fields and hedges and woods that is so essentially England seem to have a new meaning. I remember feeling most especially strongly about it in the late Summer of 1940 when I was serving in a destroyer doing anti-invasion patrol in the Channel. About that time I think everyone had a rather special feeling about the word ‘England’. I remember as dawn broke looking at the black outlines of Star Point to the northward and thinking suddenly of England in quite a new way – a threatened England that was in some way more real and more friendly because she was in trouble. I thought of the Devon countryside lying beyond that black outline of the cliffs; the wild moors and rugged tors inland and nearer the sea; the narrow winding valleys with their steep green sides; and I thought of the mallards and teal which were rearing their ducklings in the reed beds of Slapton Leigh. That was the countryside we were so passionately determined to protect from the invader.”

— Lieutenant Commander Peter Scott, 1943.

From the forward of Richard Harman’s ‘Countryside Mood’

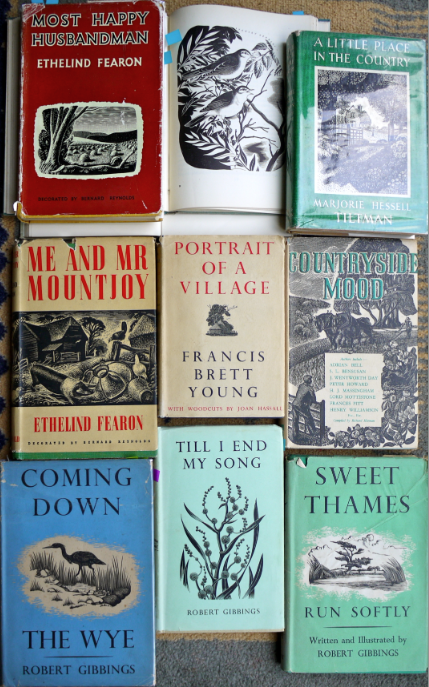

o doubt that like Lt Cmr Scott, many Britons living during either world war felt threatened by the very real possibility that their country, along with their liberty, could be snatched from them, and that their lives, together with their much loved countryside could be irrevocably changed. A sense of insecurity that fortunately most of us find impossible to imagine now. This anxiety, coupled with an awareness that rapid changes were taking place within farming and its technologies meant that many traditional ways of country life were rapidly changing and in many cases disappearing altogether. It would seem that many artists and illustrators felt the need to record and to express visually, similar sentiments to those expressed by Lt Cmr Scott. These national concerns of a disappearing Britain may go someway to help explain the proliferation of books produced between the wars (and shortly after) that graphically depict the subject of ‘the countryside’ and rural living. What’s striking about these titles is that the books were mostly illustrated rather than photographed, and more specifically they are mostly illustrated by means of wood engraving and to a lesser degree, scraperboard.

o doubt that like Lt Cmr Scott, many Britons living during either world war felt threatened by the very real possibility that their country, along with their liberty, could be snatched from them, and that their lives, together with their much loved countryside could be irrevocably changed. A sense of insecurity that fortunately most of us find impossible to imagine now. This anxiety, coupled with an awareness that rapid changes were taking place within farming and its technologies meant that many traditional ways of country life were rapidly changing and in many cases disappearing altogether. It would seem that many artists and illustrators felt the need to record and to express visually, similar sentiments to those expressed by Lt Cmr Scott. These national concerns of a disappearing Britain may go someway to help explain the proliferation of books produced between the wars (and shortly after) that graphically depict the subject of ‘the countryside’ and rural living. What’s striking about these titles is that the books were mostly illustrated rather than photographed, and more specifically they are mostly illustrated by means of wood engraving and to a lesser degree, scraperboard.

On looking at images such as the book cover of ‘Countryside Mood’, one might argue that these depictions of rural life are—and probably were at the time of publishing—a somewhat romanticised vision of Britain’s rural living. However, despite the nostalgic qualities that we might associate with the images, when one compares some of the illustrations with the then contemporary photographs, it is clear to see that some of these images were not unrealistic snapshots of what one might see in going on in the busy, more heavily human powered, pre-WWII countryside. After all, despite advances in farming technology there were many more people farming the land than today and as such, the rural populace—particularly those who worked the land—would have undoubtedly had a far greater knowledge of country ways, possessing a sensitivity to the land and its seasonal rituals that most of it current inhabitants have—if only because it was necessitated by both war and the dictates of technology.

This rise in popularity of these depictions of rural life—particularly in the form of wood engraving—appears to be attributed to two British* born artists: Claire Leighton and Agnes Miller Parker. Selbourne (2001) notes that, “By the mid-1930’s, largely due to the success of the countryside books of Clare Leighton and Agnes Miller Parker, wood engraved illustration had indeed increased in popularity, the demand for accurately rendered rural and domestic scenes reflecting the conservative taste of the British public which looked nostalgically back to [Thomas] Bewick“. Selbourne adds that Leighton “revived the British pastoral tradition for wood-engraved illustration.”

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

On this peculiar hankering for a romanticised vision of Britain, Hickman (2011) adds that “As a result of the increased importance of the countryside in English culture, publication of books on rural life for a middle-class urban readership reached its height during the inter war years. Concurrent with the popularity of rural themes was the revival of wood engraving in England as a form of creative expression, in which Leighton played a central part, bringing about a brief “golden” era of fine and popular illustrated books on country life issued by commercial and private presses.” Hickman also adds that “Leighton’s wood engravings of interwar English country life portray a rural culture barely touched by modernity, a domesticated landscape in which robust farm workers maintain a close relationship with the soil and its associated values of simplicity, stability, and diligence.”

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

From the mid 1950’s it would appear that there was a distinct and fairly rapid decline in the production of this genre of illustrated countryside books. One can only guess at why this happened. My guess is that the market simply became over saturated, ultimately causing interest to wane, and as illustrative themes and techniques move in and out of fashion, this genre simply ran its course and became outdated.

Yet despite the rapid growth of digital illustration and the trend for depicting all things urban in recent years, I have noticed that there is something of a revival of the rural illustrative genre taking place. Perhaps once again, with the increased threat of our countryside disappearing, this time at the hand of would be green belt developers, we’ll see a resurgence in artists, illustrators and photographers wanting to record images of the country for posterity. Certainly the rural themes expressed as black and white illustrations are experiencing a certain amount of renewed interest, with some publishers wanting to echo the styles this bygone era. Some of the illustrated titles from Snake River Press echo these past styles of illustration whilst adding a contemporary twist.

The incredible work of prolific Irish artist, sculptor and author, Robert Gibbings—another contemporary of Leighton and Miller Parker—has also seen his countryside titles reprinted in recent years. And as recently as 2009, Richard Harman’s ‘Countryside Mood’ was once again republished for a new generation to enjoy.

References:

Harman, R, 1943

Countryside Mood

Blandford Press

Selbourne, J, 2001

British Wood Engraved Book Illustration 1904-1940 A Break with Tradition

The British Library & Oak Knoll Press

Hickman, C.M, 2011

Clare Leighton’s Wood Engravings of English Country Life between the Wars.

Hickman, C.M, 2008

Clare Leighton’s Art and Craft; Exploring Her Rich Legacy through the Pratt Collection.